thea martin is a rock pool

an emerging Adelaide musician on all of the different bodies they inhabit

Every time I see them, Thea Martin reminds me a little of an illustration straight out of a children’s book: a wide-eyed sketch, features heavy with undisguised and swiftly changing emotion. It is the night before they will be driving nine hours to Melbourne with their Twine bandmates to perform at a smattering of gigs. Curled up into a compact ball on one of their many living room couches (there’s a wide assortment - Freudian chaise lounge, sofas made of leather, sofas made of plaid), fingering the floral embroidery that trims the collar of their shirt and talking about what their instrument means to them, they look to me exactly like a modern incarnation of Peter Pan. Boyish, girlish, small, big.

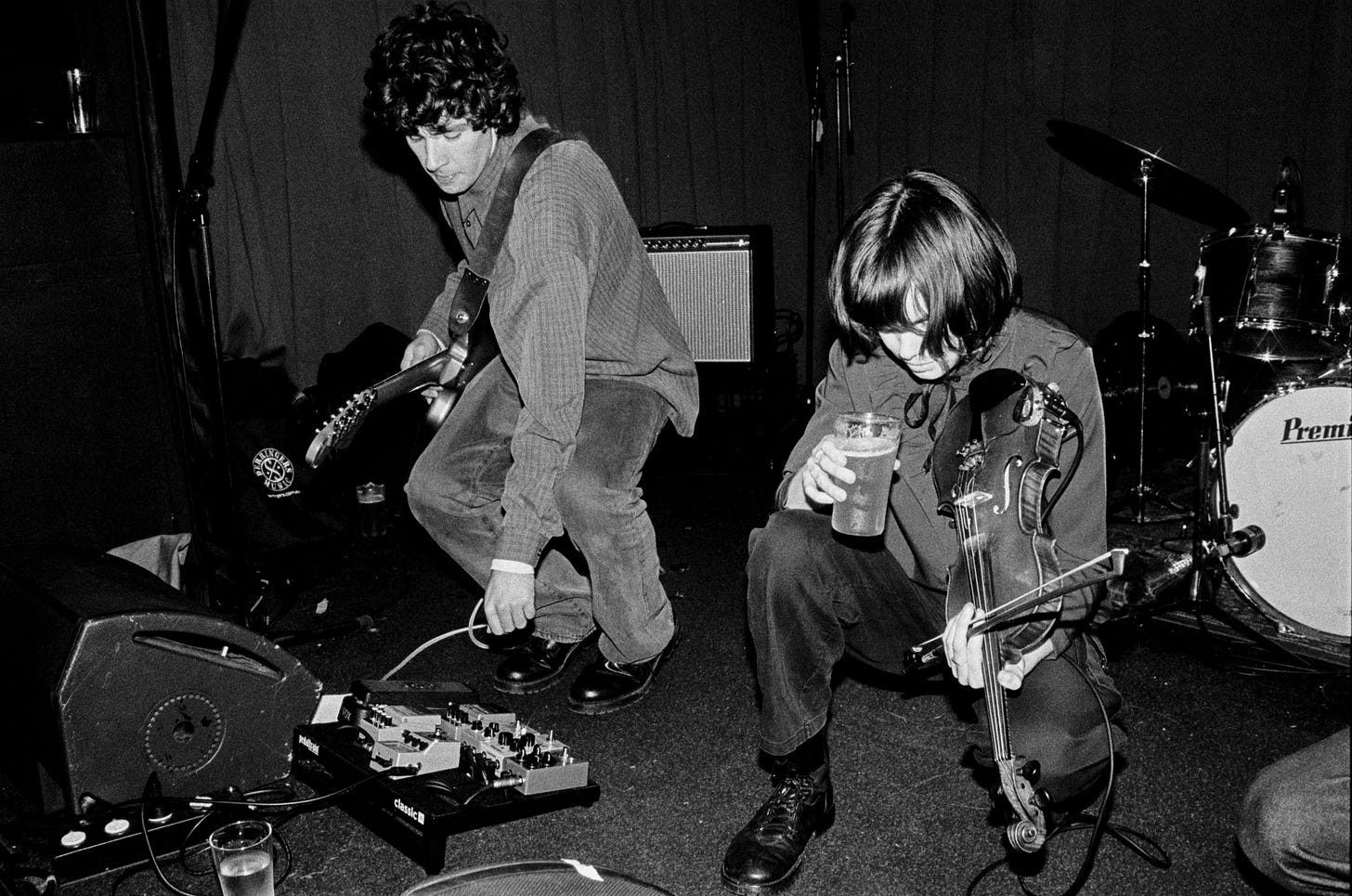

Thea Martin is a musician and music educator based on Kaurna land. They teach at four different schools, with instruction that emphasises creativity and body movement, are a co-director of the community-engaged arts organisation Connecting the Dots in Music, and created the collaborative composition workshop series A Room of Her Own Workshops. As a violinist, they are a member of five different local Adelaide bands, projects that strain broadly across genres and textures: there is Twine, the self-described “noisy band,” the holy arbiter of dirty melodies and unashamed cacophony; there is Cagefly, a classically post-rock six-piece with soaring instrumentals buoying tender introspective monologues; there is Wake in Fright, the alternative folk band, secret champions of love in song, equally beholden to cinematic imagery and sonic mischief, (when I ask the band’s frontman about the genre he feels their sound most adheres to, he becomes confused: “It changes with every album,” he says, shrugging apologetically); there is Eyrie, the heartrending, elusive folk piece with lilting harmonies and string arrangements reminiscent of crisp apples and chimney smoke (“It’s like falling in love,” my best friend whispered to me the first time she witnessed them play at the Wheatsheaf Hotel); there is War Room, the broadly post-punk project who once proudly declared themselves to be God’s least favourite band - one could posit that they are perhaps God’s silliest band, given their veritable commitment to producing giddy, indulgent, and weird sounds. (While writing this I send a quick frantic message to Louis Campbell, driving force behind War Room’s silliness, asking if I am indeed allowed to refer to War Room as “God’s silliest band.” He says it is “completely chill,” and agrees that when War Room clicks with a style, they tend to keep travelling down that path to a “ridiculous extent.” “Sincerity without sensibility,” his partner and fellow awe-inspiring musician Venus chimes in over text.)

In the space of time that I alone have known Thea, I’ve watched them inhabit many different bodies, different faces, different silhouettes and sounds both on stage and off. Their musical involvement clearly encompasses this cosmic range of style, genre, and form. I ask them what they see as the emotional through-line that connects it all.

“It’s all about my instrument,” they say. It’s all about what violin specifically can contribute to all of these projects. “Violin is considered quite a feminine instrument and has some quite gendered associations, and learning to play noise music was a way to start to subvert that and unpack it, and I feel really great about the fragility that I can bring to all of this art with my instrument.” They pause, hold themselves, hands resting on elbows. I see them shape the words in their mouth before saying anything out loud - they want to get it all exactly right. “But it’s not fragility as weakness. It’s fragility that can be really strong.” I suggest to them that fragility is a state that seems to inherently hold multiplicity within it. They agree, excited that I seem to understand immediately what they mean.

They also see common values in how all of this different music is made, in what is trying to be achieved with it sonically. “A lot of it falls into, genre-wise, an ambiguous post-rock kind of world. There’s a lot of focus on instrumental music, which I love. Cagefly plays with the emotive power of solely instrumental music and then words are woven into that almost as an additional texture rather than the primary thing behind the song. It’s the same with Twine…and War Room in its own way is doing that too: how weird can we make this music, how can we sonically defy every expectation.”

When I ask them what specifically draws them to projects, they know the answer immediately, emanating a nervous energy that seems somehow conducive to acidic clarity: “It’s always been led by people, people I want to be around, people who I think are making interesting things.” Is it always people they already know? They shake their head, bouncing giddily on the couch. “When I joined War Room, Louis asked me if I would just come to a band practice. And he picked me up and drove me there and put me in a room with these four men who I didn’t know.” Did that make them uncomfortable? “I was very nervous but I just respected all of their conviction to making interesting sounds and just so immediately felt musically at ease…It was immediately a very comfortable creative space and felt really challenging as well, and that was another reason I wanted to be part of that project. And then Twine as well I didn’t know anyone. But Twine is just my favourite kind of music, the music I love the most.” Onstage with Twine, they get to live out their “sonic dream.” They bounce on the couch one more time, and then shepherd themself back on track. “It’s just absolutely about the people, and about if it feels creatively fulfilling. But I couldn’t do something creatively fulfilling if I didn’t feel good about the people.”

I posit timidly that the kind of passion and fervour with which they make things seem conducive to potential burn-out. How do they stop themself from being spread too thin, emotionally and creatively?

They laugh, eyes wide with a tinge of hysterical alarm. “Good question. I think I’ve gotten better at saying no to things. But I’ve been burnt out for, like, four years in a row. And this is the first year where I maybe…” They hesitate, then tentatively confirm that yes, they do feel good about where they are at with their schedule right now. What makes a difference, they continue, is that they are generally not the primary songwriter within the bands that they contribute to. “I’m so often an additional sound, a textural sound, a layered sound. It’s a way for me to be creative without having to be the driving force behind that creativity.”

But do they wish that they got to be the driving force more often?

“Yes and no.” They suggest that teaching artistry is a medium where they feel that they can be the driving force - where they are, in fact, extremely good at being the driving force. “But I want to learn from other people. Like, I can just be around people and learn through osmosis and pick new things up without having to be the force behind it.” But their confidence in their own creativity when it comes to producing music has spiked over the last few years. They cite being a part of Wake in Fright as a major factor behind this personal growth. “Rehearsing with Wake in Fright was like a return to the way I made music when I was a child. Rehearsals felt very similar to the chamber music rehearsals I would do as a teenager. That kind of rigour and attention to detail…I didn’t know band stuff could be like that. That feels like a place I know. And that has made me feel more comfortable with being that person for my own projects.” They smile, allowing themself to be proud.

It seems to me that, through music, Thea is always trying to find their way back to their body and, ultimately, back to themselves. They get to experiment with unfamiliar emotions within sonic spaces, and through sound, they feel that they can fully explore temporality and corporeality - they can be no one and everyone at once.

I express to them music is perhaps a medium that allows for more fluidity than usual, especially when it comes to binary expectations of gender.

Their agreement is vigorous, acknowledging that the musicians around them have shaped how they view their own gender. “You get to go onstage and see people experiment with their identities and how they present themselves.” They cite their bandmate Jared Payne, who fronts Cagefly, as a huge inspiration to them, describing with soft awe the way that they appear to be able to just “try on” different ways of presenting and articulating themself. I ask about how they feel about the way that they present onstage - whether a sense of style, a consciously constructed outfit, feels significant to them or not. “Alicia [Salvanos, the bassist from Twine] and I talk about this sometimes, about the interesting pressure we both feel as non-men to both represent femininity and to also go against that in how we dress when we’re onstage. Because there’s this sense of, like, we want people to see that there are non-men on stage. I remember when I first started playing shows I thought the only way for me to dress was to wear my most baggy clothes and to put on the most masculine silhouette that I could and just to kind of be one of the boys - ”

And to not have a body?

“Yeah, to not have a body and to be one of the guys.” They describe the uniform of oversize cargo pants and huge baggy shirts that they used to feel was their only aesthetic option onstage.

I hesitate before asking if dressing in a more traditionally feminine style onstage feels more frightening to them. But I ask because I remember the way they trembled when they had to wear a low-cut black dress for a particular show, a dress that promised to exhibit a more womanly figure - a dress that I had given them. I ask because I remember when they had worn a delicate corset to a dinner, and the laces of it had caught on the door handle, yanking Thea’s slight frame backward. The corset came undone. They rolled their eyes at me. “My body is literally rejecting femininity right now.”

Stretching their limbs across the sunken sage-green couch, they sigh. “Just wearing anything where I have to be aware of my body perhaps is challenging. I don’t know where the line is with what doesn’t feel like me with femininity and what does. Because sometimes I do wear things that are traditionally feminine and I do feel comfortable, and then sometimes the line is crossed and I don’t know exactly where that line is. Or what causes those feelings. But I am trying to challenge myself more with that, to wear all kinds of outfits, all kinds of silhouettes. But I’m also aware that often I’ll be the only person doing that because I play with a lot of men, who perhaps experiment with their clothing a little less because of societal ideas around what it means to dress as a man.” They smile affectionately. “But sometimes they get funky with it too.”

In general, it seems, there is an element of loneliness, frustration, even exhaustion, that comes of being a prominent femme person in such a male industry, expected to be the moral compass of every band they participate in when it comes to social issues or gig protocol, expected to constantly contribute their own lived experience as a non-man to further the understanding and compassion of the men around them. But, they say, shooting me a subtly mischievous grin, they want it on the record: “I appreciate all of the men that I play with.”

Thea thinks back to being a teenager, back to an era where their clothes didn’t quite fit them right, where the other kids weren’t always kind to them, and where they stared at the ceiling and listened to anthemic indie rock religiously - a genre understandably special to misfit teenagers, something that always feels like a holy relic understood by only you when you first stumble upon it at sixteen. Its emphasis on pure, unbridled feeling, Thea and I agree, provides a sense of catharsis like no other. They remember sitting in the car with their father - they were fourteen, maybe even fifteen - listening to New Order’s ‘Bizarre Love Triangle.’ Even when the car had pulled up just outside the house they lived in and the engine had stopped running, the two of them sat there together listening in silence until the song was over. Thea remembers her father saying softly, “I think that’s a perfect song.”

“Just seeing the way that song made him feel,” Thea continues, “I was like, oh, I hope I get to do that one day with making sounds. Not to replicate that sound, exactly, but…” They steeple their fingers, brimming with desire. “To make people feel that way.”

Thea was a very different person back then, they acknowledge, but it doesn’t necessarily feel like a different era for them. They are in the habit of challenging their own notions of temporality, what time in its essence means. Unsurprisingly, the primary way in which they explore what time means to them is through sound.

But it is not merely other creators of sound that have expanded temporality for them. They cite author Virginia Woolf as a major influence on these thought processes. “I think,” they say, giggling because they are keenly aware of just how artistically masturbatory they are about to sound, “that the stream-of-consciousness style of Woolf’s writing feels the same to me as post-rock. It’s less about traditional structures and about how things can move in and out of each other and are not bound by, like, verse, chorus, verse. The way she thinks about people and the interactions between them and the relationships between people I think is something that I want to articulate with the music I make.” They talk about a song they wrote, unreleased, titled ‘Part Two: Time Passes,’ based around a section of Woolf’s postmodern triumph To the Lighthouse. Thea is fascinated by the way time is rendered in this brief portion of the novel, the way time is being played with. “Ten years pass in this small section of the book, and people die, and it’s kind of told from the perspective of this house…Music is a temporal art and I’m very interested in sonic experiences that challenge your understanding of time or make you feel timelessness or make you feel lost in time or unsure of time.”

They go on to discuss Chilean magic realism pioneer Gabriel Garcia Marquez. “One Hundred Years of Solitude, I think, is a really interesting look at time. It’s stayed with me in ways I don’t even realise. The grandiose nature of that book, but also how subtle and nuanced it is…” They shrug. “I love detail, I love nuance, and I love the mundane.” They nod. It really is that simple

.

Time intersects and plays upon the body in fascinating ways - as does sound. “When I discovered that I could use music as a vessel to reenter my body, that was a very exciting and a very healing realisation which came from years of subconsciously having this message communicated to me that the goal of my music-making was to transcend my body and avoid my body.” They sigh. “Minimising the body is such a huge part of classical music. You wear all black when you perform to hide the body. You’re told to move to the music, and then you’re told you move too much and you’re told to be still. You have to hold your body in such interesting ways. But then discovering playing in bands and being able to move and feel my body and feel what it’s capable of and push it was really helpful.” They mention discovering Pauline Oliveros, an experimental composer who emphasises healing through sonic rituals and sonic meditations. Thea describes her work as being “just so much about healing and healing through sound and healing in your body, and alternate ways of being in space and using sound for those purposes. So that’s always kind of what I'm aiming at.”

They grapple with much of their classical training, with its characteristic policing of the body, with the elitism and traditional binaries so much of that world still adheres to, especially as it is where so much of their teaching work still sits. They pose questions to themselves: “What am I doing? Is this ethical? Is this the way I want to be contributing to the world? Do I even believe in this? Is this a creative practice that I should be encouraging in young people?”

They particularly wish to challenge beliefs about constrictive gender binaries that are still so commonly upheld within the world of classical music. They describe their violin lessons as a teenager, where so often melodic phrases or ideas would be described to them as masculine or feminine. “You were told that you need to have this sense of femininity when you’re playing this section. But you’re never really taught what that is - you kind of just have to switch on all your ideas of what that might be, and the teacher either goes, yes, you did it, or no, you didn’t. It’s something that I definitely try to leave out of my teaching. And I also realised that I never really knew what anyone was talking about when they used those terms anyway.”

I ask them if, sometimes, when they are onstage playing a particular piece of music, they ever feel that the piece itself has a gender, if they believe that all music is inherently genderless, or if it contains all of the genders at once. Smiling broadly, they immediately turn the question back onto me. “I’d like to know what you think about this.”

I hesitate. I don’t know, I say. I guess for me I would imagine if I was playing music on stage…maybe sometimes when playing something I would feel more like a man or more like a woman or something in between or both at once. I shrug. Kind of similar to how one might feel during sex.

They are quiet for a moment, presumably considering the ways in which music and intimacy and sex interact. “I think music is inherently about tension and release, and so is sex. So I feel like they’re very connected. And music to me has always been about connection, has always been about intimacy, as is sex. At least in the way that I have sex. Tension and release is so important for what it means to make sound and to be in sound. I definitely feel that in the interactions I have with other musicians. It’s in the sounds that we’re producing, in the ways that we encounter each other and respond to each other in space. And I think there’s a very unique kind of intimacy that comes through making sound together. There’s something so integral to the human condition about sound and vocalising and about using your body to make sound. Which is very wrapped up in physical connection.” They squint at me and laugh. “What were we supposed to be talking about again?”

Eventually, we find ourselves back on track, discussing the notions of gender they feel they inhabit when engaged in sound. “It’s certainly a very cathartic experience a lot of the time playing music, and often catharsis feels like being in the most non-binary space of myself that I can be. I do feel most separated from binary notions of gender when I’m onstage.”

We have talked about how music has been, for Thea, something that allows them to rediscover their own body and their own identity. I wonder if they ever find the experience of corporeal grounding through music to be a negative thing, where they find themselves rooted to their body and they realise that they don’t want to be there.

They hum gently to themselves as they think. “An interesting thing that has happened at the same time that I have had this realisation about returning to my body and healing through sound is that I have also developed crazy noise sensitivity. I have a working theory that because I have spent my whole life trying to control sound and also to control my body, now that I have learned to break free of that a little bit more and have learned to focus on listening as an act of experience, it has maybe made me just so much more aware of all the sound there is. Maybe I had previously kind of guarded myself from sound because it has such a huge impact on my body.” It’s true that anyone who has spent a generous amount of time with Thea has seen them flinch at the sudden revving of a car engine, jump at any sound that hasn’t been forewarned. I watched them once nearly burst into tears when a metal chair fell over in the courtyard of a pub, emitting a noise like a gunshot.

It must be upsetting, I say, that sound, the thing that they have ostensibly dedicated their life to thus far, can affect them so severely.

“It is difficult,” they agree. “And it’s not really what I saw for my life. But those breakthroughs have felt too significant for me to be upset at the outcome. I wouldn’t change that. I prefer to be in the state that I am now - with a really increased sensitivity that is sometimes damaging and that I have to learn how to manage - than to be in this very controlled space, to an obsessive point, a space that held me back from a lot of creative experiences. I used to think that the only valuable way to make music was through technical excellence and classical training.” They shrug. Enough has changed for the better, it seems.

More continues to change: it seems to be an exciting, pivotal moment for the Adelaide music scene. “It feels like there’s such an interesting group of people, an interesting group of bands. It feels very de-centered from commercial popular music interests and goals. I feel really connected to the interstate scene through being in Adelaide and it feels really nice to hear people talk about Adelaide and the bands coming out of Adelaide, and to feel that this community is being recognised and understood in other places.”

But there is still a yearning for more, here in this small, claustrophobic, sweet city where so many are trying their best. “I wish people went to more shows. I wish we had more of a culture of people going out to a particular show or just showing up and giving the music that is happening in that particular space a shot. I just don’t see that in Adelaide in the way I do in other cities. Part of it is a population thing, but part of it is just this attitude of disinterest…” They trail off. They hold hands with themselves, their stare firm. “I just wish that people would give gigs a go more and I also wish that pay was regulated because it makes it really fucking hard to do anything when guarantees from venues are inconsistent or low. That’s not the fault of individual venues, it comes from systems higher up and it comes from the ways in which we value the arts in general and the ways in which we think about paying artists. But it makes it really challenging to have the stamina to play shows when you’re not getting paid. So I wish that was different.”

This is a pivotal moment in time for Thea Martin individually too, not just for Adelaide as a whole. They will be touring Tokyo with Wake in Fright in February next year. 2024 will also see the release of Twine’s debut album. They vibrate with excitement when they mention it. “I haven’t been so closely involved in making an album before. Twine has quite a collaborative songwriting process, so I really feel that I’ve been there for every single step. And I think the album is pretty fucking awesome.”

They lift their hands up. “And…” They glance around the room, as if nervous that someone will overhear. “I’m gonna say it.” They brace themselves. “I’m gonna release an EP of my own stuff.” The expected release date is sometime between April and May of 2024. “I feel that I have things that I want to say and share now, maybe in the most meaningful way up until this point.”

The EP will be titled Gossamer Songs. Their solo artist name, they are proud to announce, will be short snarl. “Because entanglement is too long a word for an artist name,” they clarify. It had to be snarl instead. “Shorts,” they explain, is the nickname their friends have bestowed upon them.

It’s all a lot to contend with. Thea’s body seems heavy with possibility, open to more. This musical scene is a beacon that offers so much, and simultaneously asks so much of them. I ask, with that in mind, how they manage to look after themselves.

Their voice softens. They hold themself, looking off into the far distance, though we’re still inside. “Being at home feels nice. And being around my housemates feels nice. They're not in the music scene. They come to shows, and they all care about the arts. But this is one of the few spaces that’s not in that world at all. And it really does feel like a nice breather just to be somewhere else.” They glance around, at the heavy red curtains that frame the windows, the vintage Playboy magazines taped to the wall, the glass candleholders, the rusted bikes stacked in a haphazard pile in the corner.

We wrap things up. Thea mutters to themself, barely audible, “That was awesome!”

In the kitchen, Thea asks their partner to make me a cup of coffee. I complain that I’ve left my cigarettes at home. One of their housemates (eating curry standing up in the kitchen) disappears without a word and emerges a moment later brandishing a lone Marlboro gold for me. I sit outside on a milk crate alone with my cup of coffee and my cigarette, surrounded by drying laundry and chalk marks on the pavement, fully in my body, listening. I think of the time that I once, without any explanation, asked Thea what they would be if they were a body of water. Their reply was instant: rock pool.

wow! thank you! excellent!

A fascinating read about a fascinating artist. Considered, sincere responses. Very insightful and professional writing. Joan Didion may soon have a challenger.